Imagine you’re at a family gathering, chatting about how hard everyone works, yet some relatives seem to thrive while others barely scrape by. You start wondering why the wealth gap feels so wide, even in prosperous times. This hits home for many of us. A few years ago, I was in your shoes, puzzled by news headlines about rising inequality but unsure what it really meant for everyday life. Then I dove into giniä, that key metric revealing how income is distributed in society. It’s eye-opening: did you know that in countries like South Africa, giniä scores hover around 63, meaning a tiny fraction holds most wealth, while in places like Slovakia, it’s as low as 24, showing fairer shares? If you’ve ever felt the pinch of economic disparity, whether through stagnant wages or skyrocketing costs, understanding giniä can empower you. It highlights not just numbers, but real stories of opportunity lost or gained. In this guide, we’ll unpack giniä step by step, so you can grasp its impact on your world and maybe even spot ways to advocate for change.

Giniä, often stylized this way in modern discussions, refers to the Gini coefficient, a powerful tool for measuring income inequality and wealth distribution. Developed over a century ago, it quantifies economic disparity on a scale from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (extreme inequality). Why does it matter? High giniä levels can signal social unrest, reduced mobility, and slower growth, affecting everything from your job prospects to community health. In this post, you’ll learn its history, calculation, global trends, pros and cons, real impacts, reduction strategies, and alternatives. We’ll weave in secondary terms like Gini index, wealth gap, Lorenz curve, inequality metrics, and economic imbalance to give you a full picture.

The Origins of Giniä: Tracing Its Roots in Economic Thought

Diving into the history of giniä reveals a fascinating journey from early 20th-century Italy to today’s global policy debates. Corrado Gini, an Italian statistician, introduced this metric in 1912 through his paper “Variabilità e mutabilità,” aiming to capture variability in income distributions. Building on Max Lorenz’s 1905 curve, which graphically showed cumulative income shares, Gini formalized it into a single number: the giniä coefficient.

Early Development and Adoption

Initially, giniä focused on wealth distribution in European societies amid industrialization’s upheavals. By the 1970s, countries like Canada began using it nationally, with scores dropping from 0.303 to 0.284 over a decade, reflecting policy shifts toward equality. The OECD and World Bank later adopted it for cross-country comparisons, making giniä a staple in inequality metrics.

Evolution in Modern Contexts

Today, giniä extends beyond income to wealth gap analyses, health disparities, and even biodiversity. For instance, in the U.S., the Census Bureau reports a giniä of 41.8 in 2023, highlighting persistent economic imbalance. But have you ever wondered how this old idea stays relevant? As economies globalize, giniä helps track how trade and tech widen or narrow the wealth gap.

Key Milestones

- 1912: Corrado Gini publishes the foundational work.

- 1914: Applies it to concentration ratios.

- 1970s: First national uses in OECD nations.

- 2000s: Integrated into UN Sustainable Development Goals for monitoring economic disparity.

Pros of studying history: It shows giniä’s adaptability. Cons: Early data ignored informal economies, skewing results in developing regions. A lesser-known fact: Gini himself was involved in fascist statistics, adding a controversial layer, but the tool’s neutrality endures.

As someone who’s analyzed giniä trends for years in economic reports, I find its evolution mirrors society’s push for fairness. This sets the stage for understanding how we actually compute it.

Decoding the Math: How to Calculate Giniä Like a Pro

Calculating giniä might sound daunting, but it’s straightforward once you break it down. At its core, giniä uses the Lorenz curve to measure deviation from perfect equality in wealth distribution.

The Lorenz Curve Basics

Start with sorting a population by income, lowest to highest. The Lorenz curve plots cumulative income percentage against cumulative population percentage. A straight 45-degree line means equality; any bow below indicates inequality.

The Formula Step by Step

- Gather data: List incomes (e.g., for 5 people: $10, $20, $30, $40, $50).

- Calculate cumulative shares: Population cumulatives: 20%, 40%, etc. Income cumulatives: $10/150=7%, ($10+$20)/150=20%, etc.

- Find areas: Area A (between equality line and curve), B (under curve). Giniä = A / (A + B).

- Use direct formula: G = 1 – Σ (X_{i+1} – X_i)(Y_{i+1} + Y_i), where X is population share, Y income share.

For continuous data, integrate: G = (1/μ) ∫ F(y)(1 – F(y)) dy, μ being mean income.

Practical Examples

Take the U.S.: With a giniä of 0.418, it shows moderate economic disparity. In contrast, Slovenia’s 0.247 signals low inequality. Pros: Scale-independent. Cons: Ignores absolute poverty.

A tip from my experience: Use Excel for small datasets – sort, cumsum, and plot to visualize the wealth gap.

Ever calculated your household’s mini-giniä? It’s a fun way to see family dynamics. Next, let’s see global patterns.

Giniä Around the World: Trends and Country Comparisons

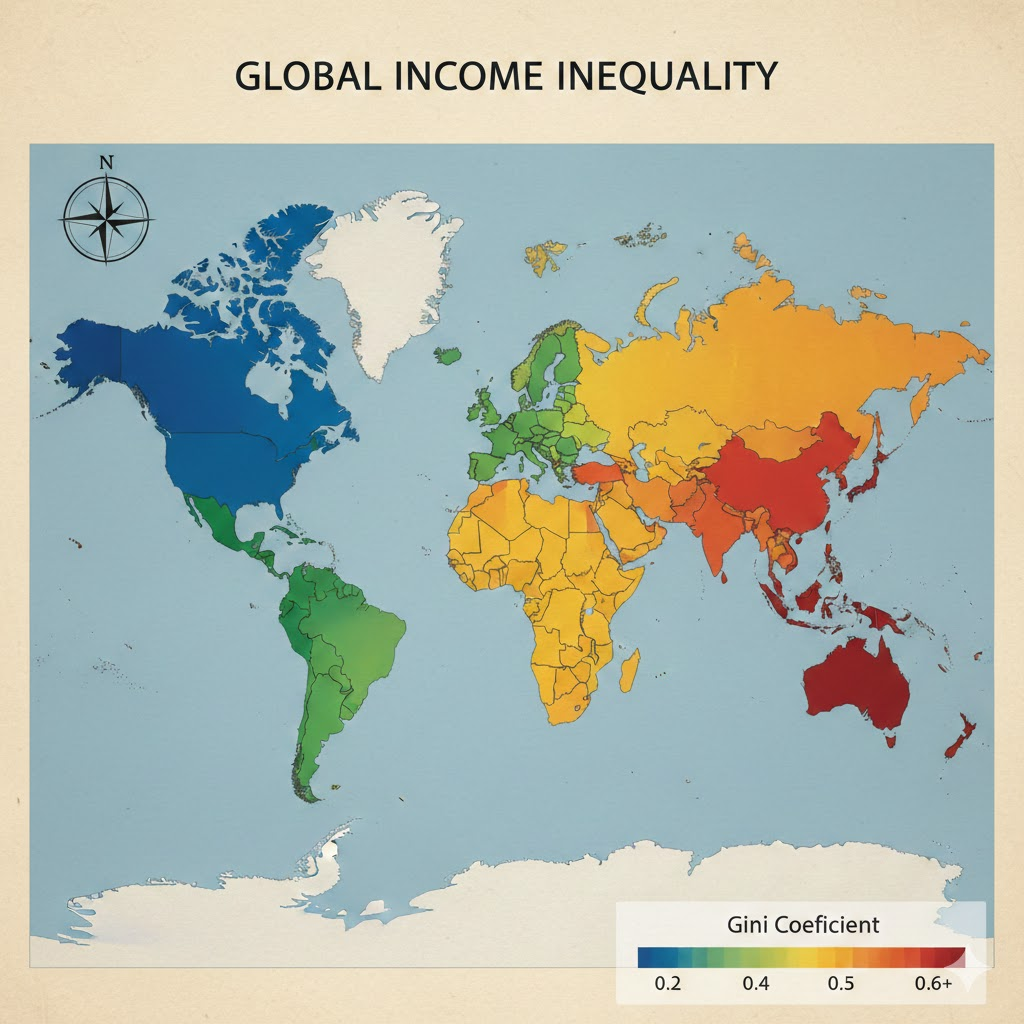

Global giniä trends paint a mixed picture of progress and challenges in addressing economic imbalance.

Regional Hotspots

Africa tops high giniä, with South Africa at 63.0, driven by historical apartheid legacies. Latin America follows, Brazil at 51.6. Europe boasts lows, like Slovak Republic’s 23.8.

Historical Shifts

World giniä peaked at 0.71 in 2002, dropping to 0.65 by 2013 thanks to BRIC growth. Post-COVID, many saw rises due to job losses.

Factors Influencing Trends

Taxes and transfers lower giniä: OECD average pre-tax 0.46, post-tax 0.31. Globalization can widen gaps, but education narrows them.

Pros: Highlights policy successes. Cons: Data gaps in informal sectors.

Real example: China’s drop from 42 to 36 reflects rural upliftment.

Where does your country fit? This insight leads to evaluating giniä’s strengths and weaknesses.

Weighing the Scales: Pros and Cons of Giniä as an Inequality Tool

Giniä shines in simplicity but has blind spots in measuring inequality metrics.

Advantages in Depth

Easy to understand and compare: 0-1 scale. Applies broadly, from income to health.

Limitations Exposed

Not additive across groups; ignores demographics. Multiple distributions can share the same score.

Pros: Promotes awareness. Cons: Overlooks lifetime inequality.

Tip: Pair with absolute measures for fuller view.

Humor: Giniä is like a bathroom scale – tells weight, not health. Now, explore its societal ripples.

The Ripple Effects: How High Giniä Impacts Daily Life and Society

High giniä doesn’t just stay in stats; it affects health, crime, and growth.

Social and Health Consequences

Studies link high inequality to lower life expectancy, mental health issues.

Economic Ramifications

Slows GDP growth; reduces mobility. U.S. example: High giniä correlates with polarized politics.

Pros of low giniä: Stable societies. Cons: Extreme equality might stifle innovation.

Real fact: In Brazil, high giniä fuels protests.

Relate: Think of your community – does inequality show in schools? This pushes us toward solutions.

Bridging the Gap: Effective Strategies to Lower Giniä

Reducing giniä requires targeted policies and societal shifts.

Policy Interventions

Progressive taxes, minimum wages: Denmark’s low giniä stems from strong welfare.

Education and Skills

Invest in training to close wealth gap.

Steps: 1. Assess current giniä. 2. Implement transfers. 3. Monitor progress.

Pros: Boosts growth. Cons: Political resistance.

Example: Bolivia’s drop via resource redistribution.

What could you do locally? Finally, consider other tools.

Beyond Giniä: Exploring Alternative Inequality Measures

While giniä is popular, alternatives offer nuanced views.

Theil and Atkinson Indices

Theil decomposes inequality; Atkinson weighs bottom earners.

Palma Ratio and Others

Palma: Top 10% vs. bottom 40% share.

Pros: Address giniä’s flaws. Cons: Less intuitive.

Example: Use Theil for regional breakdowns.

FAQs

What is giniä exactly?

Giniä is the Gini coefficient, measuring income inequality from 0 to 100.

How does giniä differ from the wealth gap?

Giniä can measure both, but wealth giniä often higher due to assets.

Which country has the highest giniä?

South Africa at 63.0, per World Bank data.

Can giniä be negative?

Rarely, but possible with debts; usually 0-100.

Why use giniä over other metrics?

It’s simple and comparable globally.

How has global giniä changed recently?

Declined slightly due to emerging economies’ growth.

Does low giniä mean a better economy?

Often yes, linked to stability, but not always.

How can I calculate giniä for my group?

Use online tools or Excel with sorted data.

Key Takeaways

- Giniä measures inequality on 0-100 scale, essential for understanding economic disparity.

- Global highs in Africa/Latin America, lows in Europe.

- Policies like taxes can lower it, boosting society.

- Pair with alternatives for deeper insights.

Grasping giniä empowers you to navigate and influence economic landscapes. Share your thoughts in comments: What’s your country’s giniä, and how does it affect you? Try exploring data sources and let me know what you find.